Where Are They Now? Yann Seznec

Yann Seznec was one of the first artists to be involved with NEoN digital arts festival, way back in 2009. In 2012 he returned for a collaborative piece with musician Matthew Herbert, for which he created an entirely new instrument – the Sty Harp. For our Where Are They Now? series we caught up with Seznec and discussed what it means to be a sound artist, the 13th century Muslim polymath al-Jazari, and the pressure to over-record everyday life.

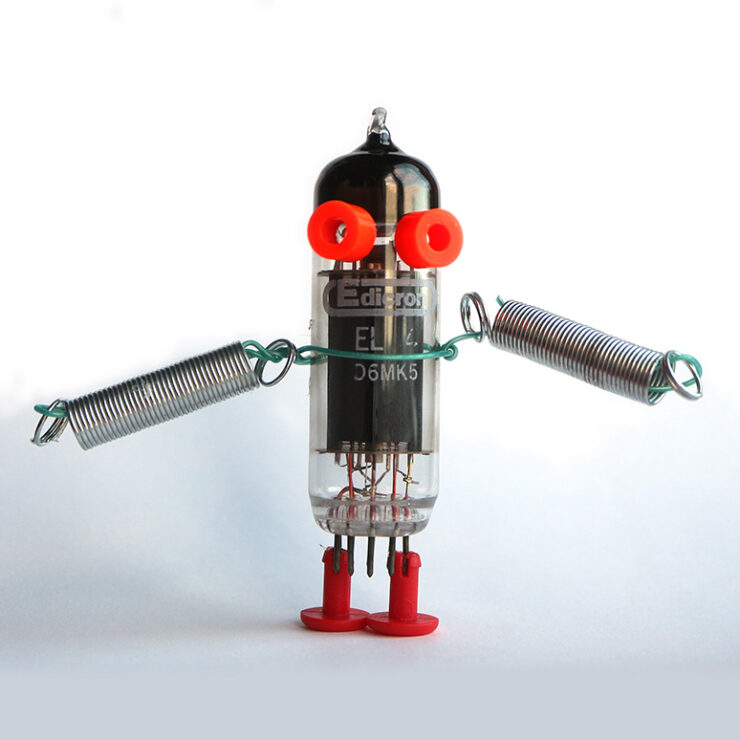

The work you exhibited in the first show, Gelkies, was presented as a sort of zoo featuring these adorable little electronic creatures made of plastic bottles that chirp happily at each other. I understand this was part of a Digital Media Artist residency at the University of Abertay. Did you ever develop this idea further, and how did you find the residency?

I was really excited to be a part of NEoN in 2009. I suppose this was partially because I felt like I was at the beginning of something really new and fresh and vibrant, which seemed like it was a perfect match for all of the interesting stuff that was already happening in Dundee at the time. It was also a fantastic opportunity for me, as I had only just started out on my career and it was my first real outing as a digital artist, rather than as a musician or teacher or Segway tour guide or whatever I had been doing before.

The residency was brilliant for me. It came at the perfect time, right as I was trying to start a new career in Scotland after getting my masters degree in Edinburgh. In the long run I ended up making connections and friendships in Dundee in general and at Abertay in particular that I kept throughout my whole time in Scotland – I ended up teaching at Abertay, thanks in no small part to the residency, and I collaborated numerous times with my Dundee friends over the years.

The Gelkies were my first foray into what became a running theme in my work – exploring technical systems and pushing them to do things they perhaps aren’t designed to do, in order to reveal underlying concepts that reflect our relationship with technology. Whilst I don’t think I specifically used the Gelkies for any future projects, I certainly pursued the same themes in a number of future projects, and I also have built a number of instruments and sound making devices that use the same underlying technology.

In 2012 you returned for a collaboration with Matthew Herbert. How had the festival changed and how did it feel as an artist to be invited to come back?

NEoN had already gotten much bigger by then! It’s been fantastic to watch it grow, and it was great fun to be a part of it again. We played our One Pig show, which remains one of the highlights of my career. It was particularly fun to bring the band, as they were all very much from London and I enjoyed showing them how great it was in Scotland.

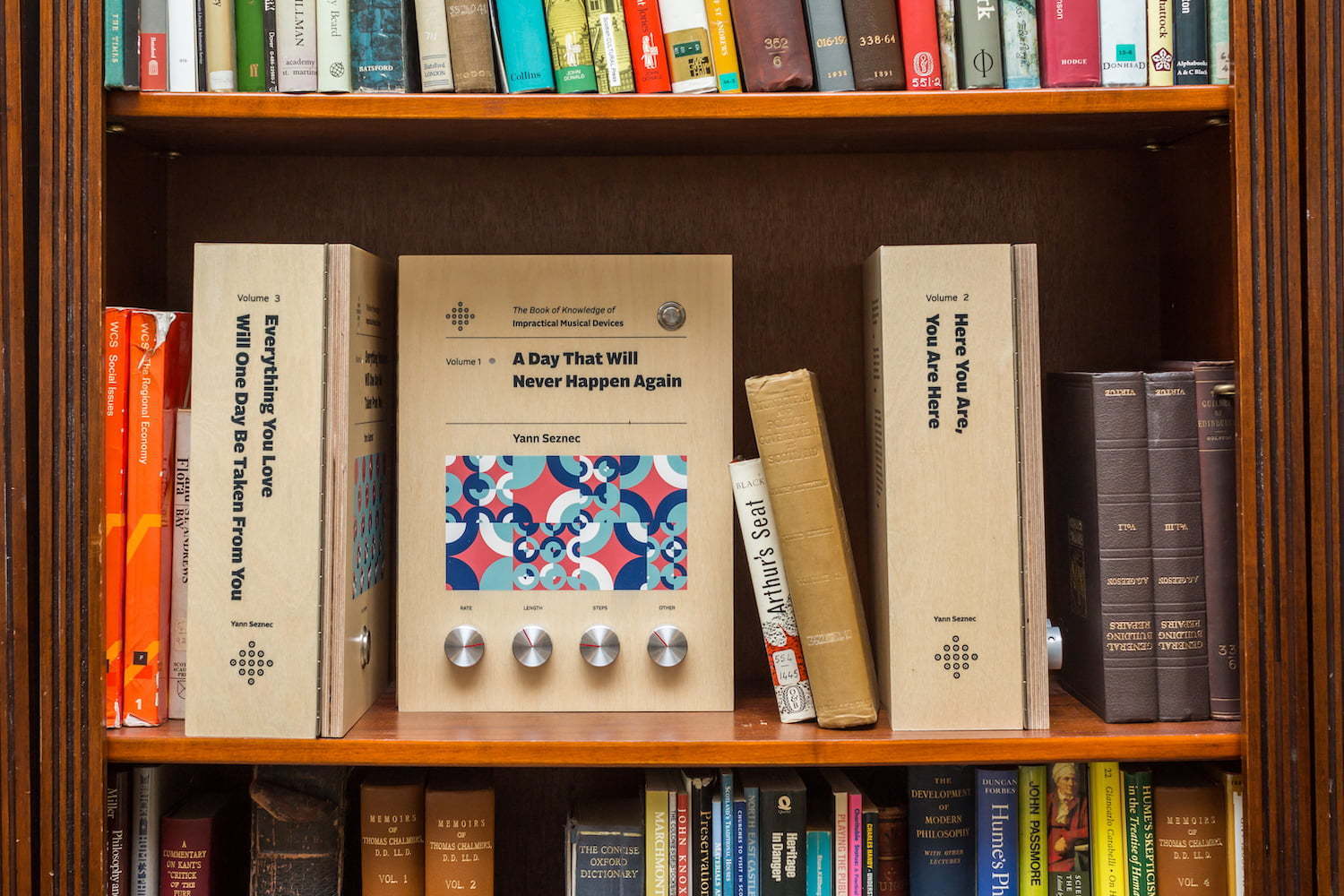

Your most recent project, The Book of Knowledge of Impractical Musical Devices, is partly inspired by the Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices written in the 13th century by Muslim polymath al-Jazari. Are you hoping your project will raise awareness of his work?

I certainly think that the original Book of Knowledge by al-Jazari is generally overlooked, as it is a completely wonderful thing that can be seen to symbolize so much. It was part of a trend during that time period of not only technical innovation but also a real focus on documentation and sharing information, which has some parallels to today. But of course if you dig slightly deeper the context gets even more interesting – al-Jazari was able to do all of this work because he had a wealthy patron, and he was essentially a house engineer whose job was to make wonderful things that glorified his employers (and, to a lesser extent, God). So whilst he was undoubtedly a genius, he was also forced to ply his trade within the funding constraints of his time, and structure his work in response to the money that was available, which is of course pretty relevant today too. This was one of my motivations for making my funding application for the project publicly available.

So far you have three aspects to the project. I was particularly touched by Volume 1: A Day That Will Never Happen Again. Do you think there’s a pressure to over-record everyday life, the – as you call it – sound trap? Have you listened to the recording again since you made it? Do you think your young son will ever listen to it?

There is certainly a pressure to over-record everyday life, and that is one of the main themes of the project overall. When I set out on making the instruments I was initially focused on creating things that somehow criticized the state of music technology, but I quickly realized that I was making a project that was really about media consumption in general, as seen through the lens of interactive sound. It became a platform for me to look critically at my own use of media, thinking about why I make recordings.

My conclusion was that I was making recordings as a way of denying that the moments I was remembering were in the past and would never happen again. I was outsourcing my memories to recorded media, which helped me pretend that I could revisit those times again. So I tried to make instruments that reflected how my memory was really working, whether it was as a scattered set of half-remembered moments, or clouds of lost snippets of time, or a slow degrading sound that will never be heard again. Of course it was certainly a class “new dad” art project too, and I’m not sure whether my son will ever play with them (though he did help me with the first sound I recorded into Volume 3!). In a way I ultimately hope that he and his generation develop a healthier relationship to media than what we have, rendering the entire project obsolete.

Volume 1: A Day That Will Never Happen Again

Can you tell us a little about the Jingle Generator you’ve been working on for Agency of None?

The Jingle Generator was such a fun project. I loved the main idea behind it that Lyall and Ryan brought to me – they wanted something that would create a new jingle for their podcast each time they recorded an episode. However, because it would be the main theme of the show, it needed to be recognizably similar, without being repetitive. This really reflected my own interests in terms of playing with randomness and repetition in sound (something that is really important in game sound design, for example). So I worked up some software that would take a static library and remix it in a different way every day that is was used. Ryan then designed a wonderful concrete holder for it, which just feels so solid, and it turned into a really fun sound-making object.

Jingle Generator

Do you have any advice for young artists, in terms of getting involved with festivals and keeping up creative momentum over the years?

I think the most useful thing I’ve learned recently is to pursue your “less good ideas“, as described by William Kentridge. Very often as artists we can get too focused on our original ideas, which generally are not very good when seen all the way through. The best work often comes from the fringes, the thinking around the edges of the original idea, the things that emerge when you really interrogate a question and push it as far as it can go. My best creative momentum has been generated by not being too wedded to ideas, but rather reacting and responding to how they develop.

In my experience this works really well with collaborators and people who want to showcase work as well – nearly all of the big projects I’ve been involved with in the past few years have involved major changes, and in each case the festival or venue I was working with was very pleased to support the thought process and creative development. I think part of that was about having the luxury of working with some really amazing people like NEoN, or the Edinburgh Art Festival, or Sanctuary Lab, or Timespan – but a large part of it is also about not being afraid to adapt and change your work when it needs to be changed.

Would you describe yourself as a sound artist? What does that term mean to you?

I often describe myself as a sound artist. I don’t mind it as a phrase, mainly because other disciplines have similar terms to designate the specific materials or methods they use (painter, dancer, sculptor, etc), so why not us? Of course it’s a term that can be taken in any number of different directions, but that’s the case with any of those. In my case I am also very interested in interaction and technology, but I think those things can be easily folded into “sound art”. It’s nice to have a term that focuses my own thinking, and I’m uncomfortable with describing myself purely as an “artist”, if only because it implies that I’m capable of producing work in other artistic fields – which is absolutely not the case!